Step out on an Indian street and ask random passers-by to name two festivals. The names you will hear most are Diwali and Dussehra. Both these festivals are widely celebrated in India. But some communities do not celebrate these festivals at all, and some even observe this as a day of mourning. This article explores some of these contrarian stories.

Detour: But first, why is Diwali celebrated? This short video explores the many different stories behind Diwali: WHY DO WE CELEBRATE DIWALI?

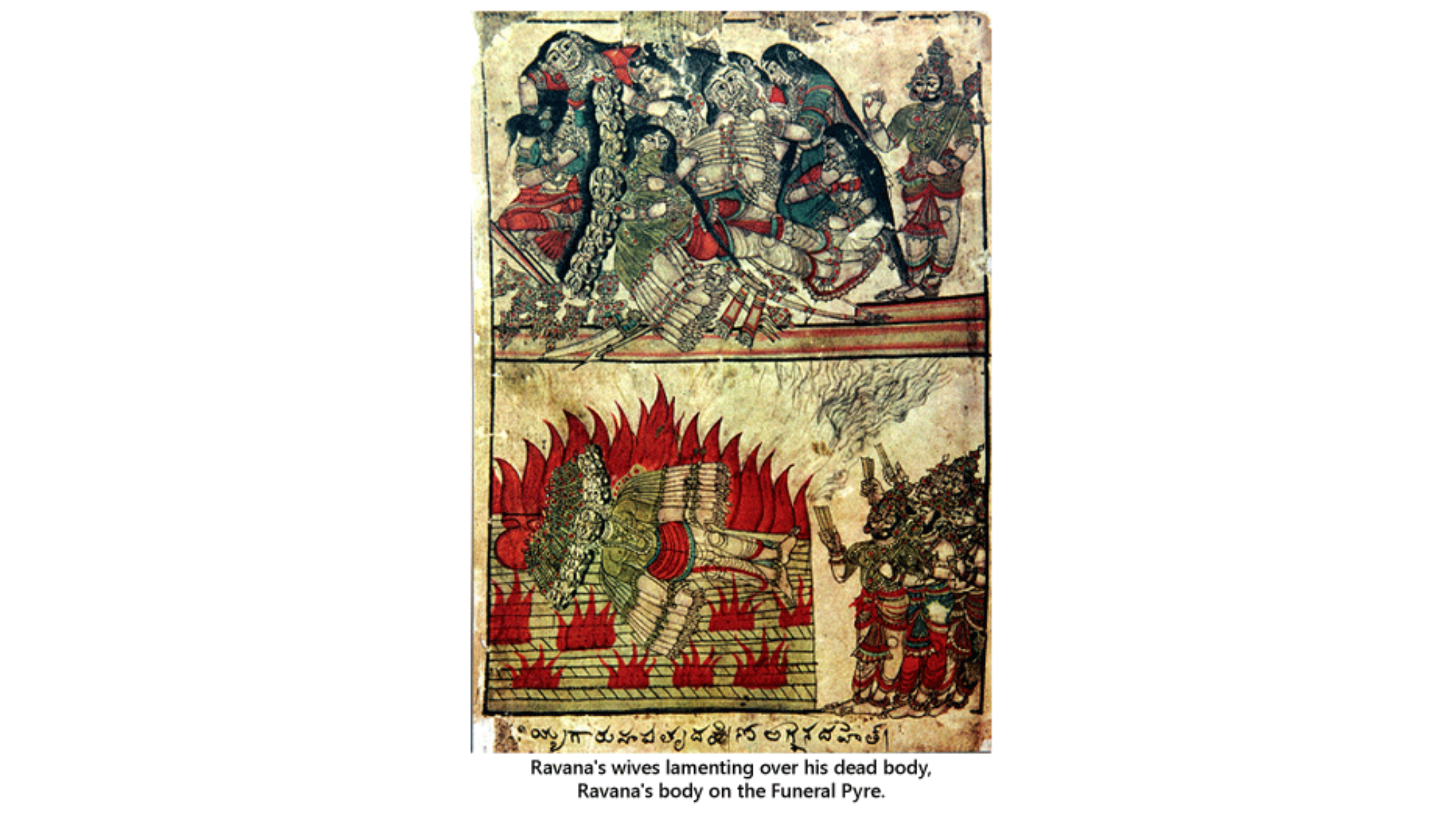

In North India, people draw inspiration from the Ramayana epic. In the story, Ravana, the Demon king of Lanka, kidnaps Sita, the wife of the righteous king Rama. Rama wages a just war on Ravana, kills him and rescues Sita. Dussehra celebrates the slaying of Ravana, and Diwali celebrates Rama’s victorious return to his kingdom of Ayodhya. But some communities in India have a very different take on Ravana: they believe that his good qualities have been underplayed. Some even quote the scriptures to back it up.

The scriptures say that Ravana was the son of the holy sage Vishrava. Ravana was an ardent devotee of Siva, the supreme God. Once, he even chopped his own 10 heads to obtain the grace of Siva! He was a religious master with spiritual powers. So, these contrarian communities ask, why would we celebrate festivals that vilify him? Let us look at their perspective.

Close to Delhi, is the village of Bishrakh in UP. People there believe that ‘Bishrakh’ comes from ‘Vishrava’, Ravana’s father. They say that Vishrava installed a Siva idol in their village, and that Ravana was actually born there. That makes Ravana a true son of the soil. How can they celebrate his fall?

From the story of the son, let us move on to the story of the son-in-law. The Ramayana says Mandsaur in MP was the birthplace of Princess Mandodari, Ravana’s faithful wife who stood by him through thick and thin. To the people of Mandsaur, Ravana is their son-in-law! How then, can they celebrate the defeat and death of Ravana? They don’t.

Mandore in Rajasthan ignores Diwali too. According to local tradition, Ravana married Mandodari in Mandore. The local priests, Maudgil Brahmins, believe that when Ravana came here for his wedding, their ancestors accompanied him.To them, Ravana is like a son-in-law, so they do not burn his effigy during Dussehra. Instead, they perform the Shraad, which is an annual ritual seeking peace for the departed soul. They believe Ravana was more good than evil; it was just bad luck that he kidnapped Sita and paid the price for it. Even today, there is a shrine for Ravana in Mandore, and the locals believe that worshipping there will give them spiritual powers.

Temples to Ravana are not uncommon. The Ravangram temple in Vidisha, MP is said to have been consecrated by Kanyakubja brahmins – the subsect to which Ravana belonged. There are Ravana temples in Kakinada (Andhra) and Kanpur too.

The people of Baijnath village in Kangra, Uttrakhand do not worship Ravana, but respect him as a great devotee of Siva. According to locals, Ravana offered his 10 heads to Siva while doing penance in this village, and Siva blessed him right here. They see no evil in Ravana, and do not want to celebrate anything that celebrates his defeat and death. The markets are closed during Dussehra and Diwali and people do not buy sweets or fireworks. They are against the ritual burning of Ravana’s effigy during Dussehra, because they believe it will bring divine wrath on them. Local folktales speak of people who neglected this advice and suffered severe misfortune.

The Gond tribals Gadchiroli in Maharashtra reject the scripture version of Ravana: a kind of ‘media conspiracy’ theory! They call themselves ‘Ravana-vanshis’ – meaning ‘descendants of Ravana’. They worship Ravana and his son Meghnad as gods. Their story is that Ravana was a Gond king who was attacked by ‘Aryan invaders’ (probably a reference to Rama) and unjustly killed; and the abduction of Sita never happened. They say that Valmiki, the author of the original Sanskrit Ramayana epic, did not consider Ravana evil; it was the later version by Tulsidas that painted him as evil. Unfortunately, say the Gonds, that interpretation has stuck in people’s minds.

Some communities do not celebrate Diwali for historical reasons, For example, the Mandyam Iyengars (a priestly class) of Melkote in Karnataka observe Diwali as a mourning day. In the 18th century, the Mandyam Iyengars owed allegiance to the Wodeyar kings of Mysuru, their long-time benefactors. They worked secretly to secure an alliance with the British to help the Wodeyars fight the expansionist neighbour Tipu Sultan. Tipu got wind of this deal. On the day of Naraka Chaturdasi (Diwali), 1790, he attacked Melkote and killed at least 800 unarmed members of the community. After that, the entire community never had the heart to celebrate Diwali.

And some communities do not celebrate Diwali for ecological reasons! The Thoppupatti and Saampatti villages near Trichy in TN have decided not to celebrate Diwali. The fireworks of Diwali disturbed the bats living in the branches of their sacred banyan tree. They consider the banyan tree sacred because it is home to their Village God, Muniyappa-Saamy. The rural folk near Vettangudi bird sanctuary never burst crackers during Diwali, as a consideration for migratory birds. And the Forest conservation officials distribute sweets to them on behalf of the birds!

Isn’t there a charm in all these contrarian stories of India?

Read more about about the stories behind the customs associated with Diwali in this blog: Tales of Diwali and Deepavali

This blog explores stories of another popular festival, Navaratri: Kolu – Toying with tradition

Image Attribution:

1. Statue of Ravana at Koneswaram Temple, Sri Lanka – By Gane Kumaraswamy – originally posted to Flickr as Ravanan – King of Lanka, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9906203

2. Statue of Ravana at Mandsaur – By Rohit MDS – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45252132

3. Miniature painting of Ravana’s wives lamenting over Ravana’s dead body, c. 17th – 18th century – By Andhra Paintings of the Ramayana – http://www.artnewsnviews.com/view-article.php?article=discovery-andhra-paintings-of-the-ramayana&iid=21&articleid=530, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18323541

4. Relief of Queen Mandodari and the women of Lanka mourning the death of Ravana at Prambanan temple, Indonesia, c. 9th century – By Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8611253

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020