Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) began as a painter of coaches in a workshop. Yet, deep down inside, he dreamt of being a great landscape artist. After a couple of years of coach painting, he got a chance to study at the Royal Academy of Arts. After graduating, he produced a number of landscapes during 1772-84; but these brought him neither glory nor wealth. Ultimately, he decided to seek his fortune in India.

That was a smart life-changing decision, for, India was the “happening” place in those days. The British East India Company was no longer a mere trader; it actually ruled vast Indian territories, bringing humongous wealth to England. By now, interest around “exotic” India had peaked. This was the pre-photography era, hence British artists toured India and brought back images to satisfy this curiosity. They were usually portrait painters: they captured images, but not the public imagination. This was Thomas’ golden opportunity!

The East India Company controlled the sea-passage to India and would not allow “undesirables” on their ships. Thomas made himself more marketable by describing himself as an “Engraver”. That was stretching the truth — for he had not yet mastered engraving at that time — but a successful ploy. In 1785, he and his 15-year old-nephew William (designated as “Engraver’s Assistant”) sailed via China to Calcutta.

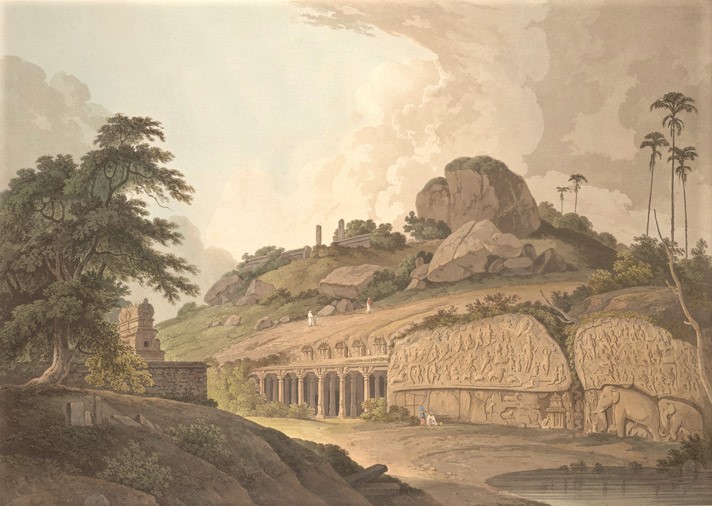

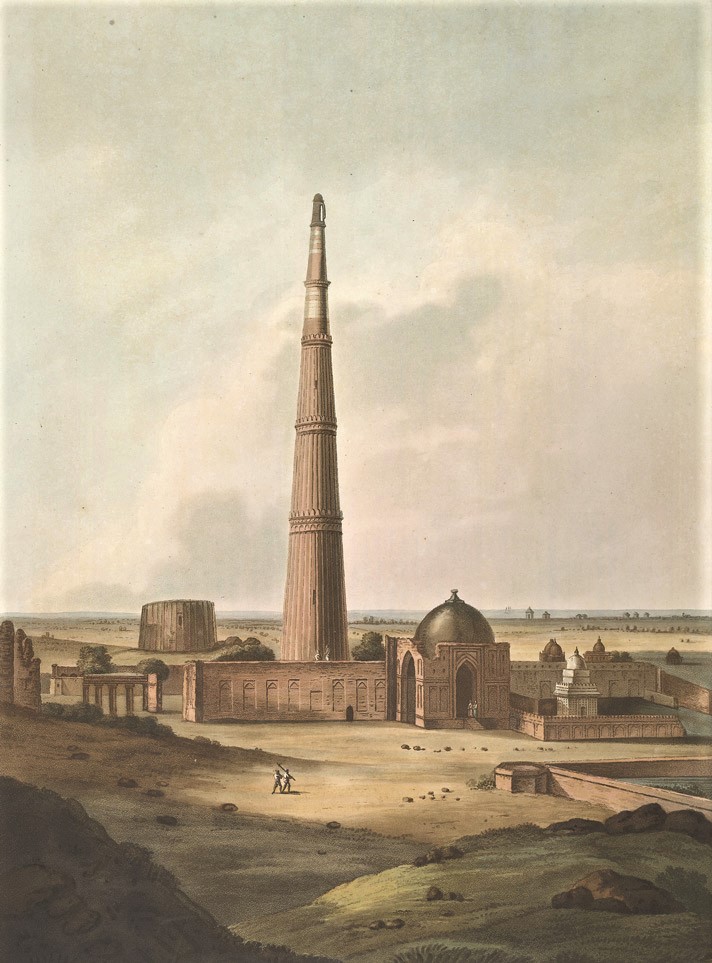

The uncle-nephew duo chose their subjects thoughtfully: places of natural beauty and important historic sites. In 7 years (1786-93), they travelled all over colonial India and the princely states with a retinue of palanquin-bearers and coolies: they sailed up the River Ganga, walked on the Himalayan foothills, and touched the southern tip of the Indian peninsula, before finally sailing back from Mumbai. They had travelled thousands of kilometres before the railways were even invented! Their journeys must have been even more arduous, because they travelled with heavy equipment and supplies. Here is a sample of their art

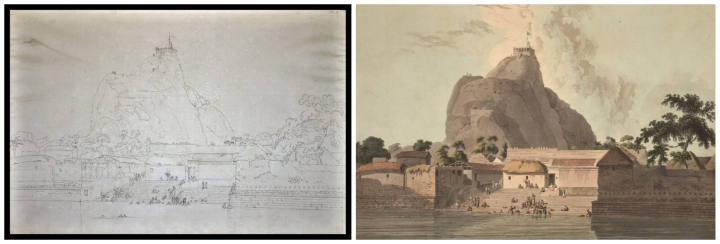

At every site, they would first decide on the best viewpoint using a camera obscura (an optical box to project the scene on a screen). Then, they would refine their perspective using a perambulator (a surveyor’s wheel for measuring distances). Finally, they would set up their drawing tables and make accurate pencil or pencil-and-wash drawings. William kept a detailed diary of all the subjects they ‘captured’. The Daniells returned to England with a large number of sketches and reproduced them as aquatints from their studio.

An aquatint is an etching similar to an engraving, but with colour. Aquatint gives a better depth and tonal quality than simple watercolour, when printing. This project took them several years (1795 -1808). They published a six-volume pictorial travelogue called “The Orient”, and the hungry public lapped it up!

In the following years, they published similar travelogues of China and Egypt. Thomas was now much in demand for landscaping gardens of aristocrats. He became a Royal Academician and Fellow of the Royal of Society of Arts in 1790. William became an accomplished aquatint artist himself, mostly covering the English outdoors; he too became a Royal Academician in 1822. Thomas died at the ripe old age of 91. He never married; William was his closest kin and Thomas outlived him. Their creations are etched in history forever. And yes, Thomas was right: India earned them all the glory and wealth!

Join Storytrails on the Once Upon a Madurai Trail, and witness the inspiration for a scene from Daniell’s beautiful paintings for yourself. You can also download the Stoytrails Audio Tours App and walk through some more beautiful sites that inspired Daniells including two of the Mamallapuram Audio Trails: The Shore Temple and Five Rathas Trail and The Monuments around Varaha Cave Trail. Here are some examples of what you may discover:

Acknowledgements: All pictures belong to the public domain. The author gratefully acknowledges that the portrait of Thomas Daniell was sourced from Wikipedia and all other paintings were sourced from the British Library.

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020