The first contact between India and Portugal was when Vasco da Gama landed on the coast of Kerala in 1498. Over the next century or so, the Portuguese would become a permanent fixture in Goa, using it as a waypoint in their dealings with the islands of SouthEast Asia. In all their time in India, the Portuguese were not the friendliest lot.

They had a very clear goal in the East: make heaps of money through trade and colonisation. So they had little interest in the culture and knowledge of these faraway lands. But there were some exceptions. One such exception was Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese physician, who wrote one of the first books printed in India. This landmark book, Conversations on the simples, drugs and materia medica of India (Colóquios dos simples e drogas he cousas medicinais da Índia) was a treatise on medicine published in Goa, all the way back in 1563!

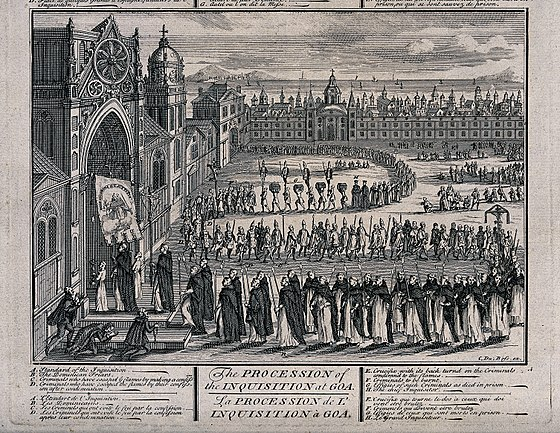

But what was Orta doing, learning about medicine in India in the 16th century? It begins with something nobody expects – the Spanish Inquisition!

For many centuries in the medieval era, Spain was ruled by a series of Muslim rulers. They called it Al-Andalus. But after the Christian recapture of Spain, there came the Spanish Inquisition, a violent backlash to root out all non-Christian influence. Garcia de Orta came from a Jewish family that had been coerced to convert to Christianity. Despite having a bright future ahead of him as a doctor, Orta was terrified of the Inquisition. In 1534, he got an opportunity to flee to India, and he grabbed it.

The early 1500’s marked the beginning of the Portuguese presence in India, and they did not come in peace. It was a violent and bloody time but none of that appears in Orta’s book. Instead, we find him focusing on the benefits of aloe vera and ginger, the joys of cashew, clove and mango and the pleasures of bhang and opium. Orta was engaging with India on his own terms.

For many years, he was the personal physician of Burhan Nizam Shah, the Sultan of Ahmednagar, who seemed to have a high opinion of the Portuguese. At the sultan’s court, he interacted with Muslim hakeems and Hindu medical practitioners, quietly picking their brains. He didn’t blindly absorb this “exotic” tradition. Instead, he integrated it with his own experiences and medical frameworks. The Colóquios spend a lot of time talking about legendary Greek physician Galen, Arab polymath Ibn Sina and the other pillars of “Western” medical thought.

He came to be widely respected in Portuguese India, receiving the leasehold of a barren island named Bombay on which to build a home. In fact, when the British took over those islands more than a century later, their Town Hall was built on the site of Orta’s old mansion.

But this little oasis of safety that Orta found in India did not last for long. In the 1540s, the Inquisition came to India. In 1543, Jeronimo Dias, a physician and Jewish convert – just like Orta, was convicted of heresy and burned in Goa. Through the protection of powerful friends, Orta managed to avoid punishment, dying a natural death in 1568. But sadly, the story doesn’t end there. His family was targeted after his death and confessions were wrung out of them through torture. The worst came when Orta’s body was actually dug up and burned in a posthumous public denouncement.

While the horrors of that time are not forgotten, Garcia de Orta is seen as a Portuguese national treasure today. His face can even be found on their banknotes. But most heartwarming of all, given that “orta” means “garden” in Portuguese, there are gardens in Lisbon and in Goa that are named after him. When residents take refuge from the bustle of the city in the quiet shade of a lush garden, they reenact a more pleasant version of Orta’s life. Isn’t that what he was doing as well? Taking refuge from a harsh world and finding a cure in herbs and flowers.

For more stories about the interesting characters who made Mumbai their home, join us on The Bombay Story– a walk through the streets of South Bombay with Storytrails.

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020