Today, our biggest salt-related struggle is how much to add when we’re cooking. Recipe books tell you to add “salt to taste” but they don’t tell you whose taste – yours, your mother’s or your weird uncle’s! But in the 19th century, salt was not just a kitchen dilemma, it was at the centre of government policy. In 1885, tax on salt was the third-largest source of revenue for the British Raj.

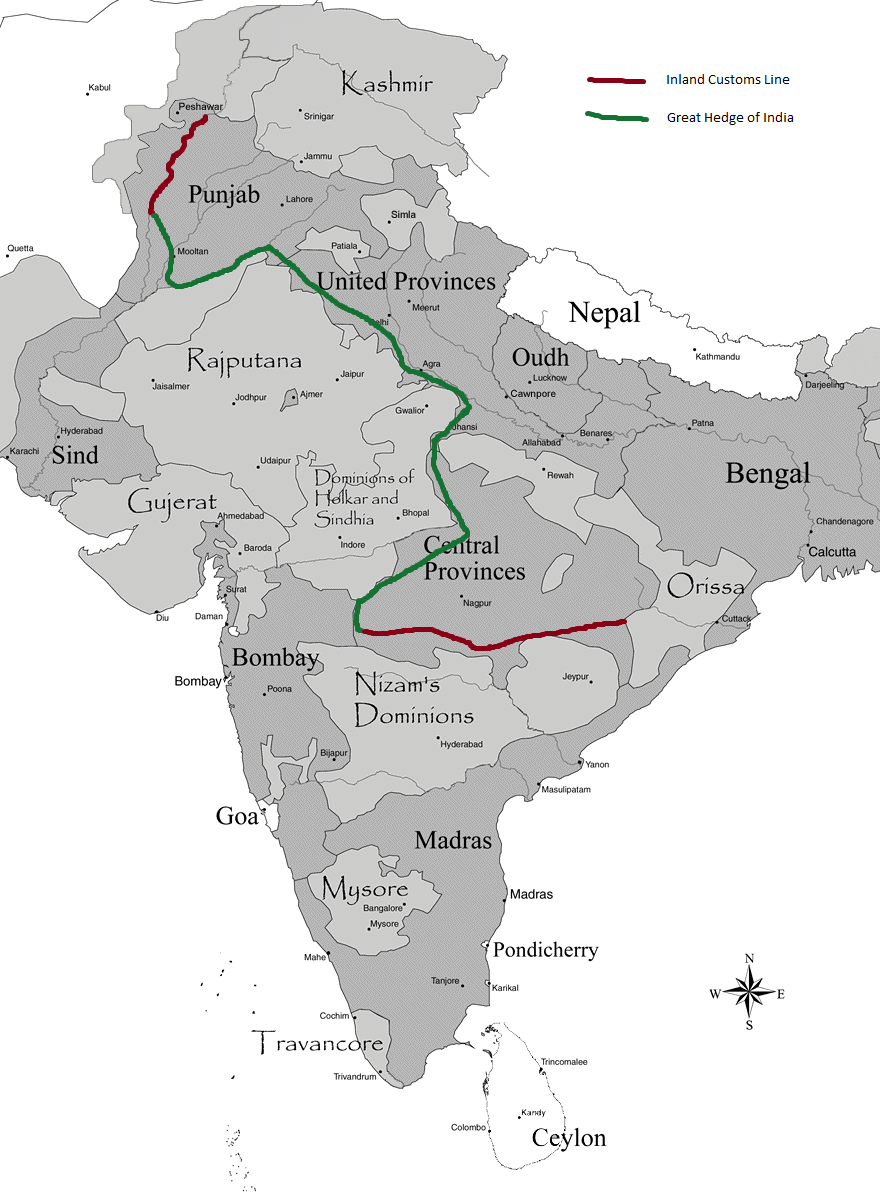

To stop smugglers trying to avoid the tax, the British instituted the Inland Customs Line, which grew as their own territories expanded. The Inland Customs Line was essentially a line of check posts to collect tax on salt coming from outside British territory. But because the line snaked from Punjab to Odisha, almost half the country, the tax was hard to enforce and smugglers were constantly making clandestine crossings. So, the British began to build a wall of prickly thorns and bushes that they assumed would stop the smugglers’ carts and wagons in their tracks.

We don’t know whose idea this was but we do know that this hedge was greatly expanded in the late 1860s by Allan Octavian Hume when he was the Commissioner of Inland Customs. Hume, of course, is most famous for co-founding the Indian National Congress. By 1878, this hedge of dwarf Indian plum trees, babool trees, prickly pear, bamboo and other plants stretched for more than 1500 kilometres and was staffed by more than 12,000 guards and officials. They had been working on it for at least 30 years. It was undoubtedly an impressive barrier – often more than 10 feet high and 6 feet thick – but it was also ridiculously difficult to maintain. Where the hedge wouldn’t grow properly, they would bring in dry brush from elsewhere and build an artificial barrier. This involved up to 250 tonnes of dry branches and brushwood per mile to shore up these sections.

Did it work?

Well, it was definitely a mammoth project. And completely mad. For all that work, all smugglers had to do was throw sacks across to waiting accomplices. Or, of course, they could just burn parts of it down. But while it’s wonderful to laugh at the incompetence of the British, their prickly wall of thorns and the invisible customs line hides a painful history. High taxes on essential commodities like salt disproportionately affected the poorest citizens of the country. In times of famine, when food and money become scarce, like during the famine in Bengal in 1943 were more than 2 million people died, the inability to buy salt could’ve contributed to the huge death toll. Salt is an unassuming substance but the human body can’t survive without it. The British never had a policy of lowering the salt tax during times of famine.

So, if some of the British did not agree with the system how did it survive?

By 1879, the great prickly hedge of India, which one British officer had compared to the Great Wall of China, was abandoned. Why? There were financial reforms and some of the viciousness of the salt tax went away but not all of it. In 1930, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would choose the non-violent boycott of the salt tax as the centrepiece of his agitation against the British. While Gandhi’s satyagraha didn’t overturn British policy, it became one of the most iconic moments in Indian history and acted as a major catalyst of the freedom movement. The salt tax was only abolished after India’s independence by Jawaharlal Nehru.

So, what happened to the hedge?

Historian Roy Moxham travelled across India in 1996 trying to trace the hedge, but couldn’t find any sign of it at all. Nobody seemed to have even heard of it. Just as Moxham was about to quit in frustration, he met an old priest in Airak in Uttar Pradesh who remembered where some remnants of the hedge could be found. It turns out – in a delicious coincidence – the priest was a dacoit in his younger days!

Want hear more stories about the British Raj in India? Come take the British Blueprints tour with us in Chennai!

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020