After losing a major battle, Humayun lived as a refugee far from home in Sind. It is where he found love and married her.

The name Humayun means “fortunate”, but ironically his life was anything but that. It was filled with unfortunate events compounded with his own failings – poor judgement of people, substance addiction, procrastination and lack of focus. History books may project Humayun as a dull interlude that must be endured, sandwiched as he was between two very successful Mughal emperors – Babur the aggressive adventurer, and Akbar the astute administrator. But there were many interesting moments in his life, particularly his pursuit of love and marriage to Hamida Banu Begum, the mother of the future emperor Akbar.

It was the year 1541. Humayun was on the run after losing major battles against the Afghan usurper Sher Shah Suri. After a very arduous journey, the fleeing Mughal entourage reached Sind where the Sultan of Thatta gave them refuge. Humayun’s immediate family and the family of his stepbrother, Hindal Mirza, found temporary peace. Hindal was once Humayun’s rival to the throne, but had now turned Humayun loyalist. Hindal’s mother (Humayun’s stepmother) Dildar Bano, arranged for a banquet to celebrate their deliverance. It was at the banquet, that Humayun first noticed Hamida Banu Begum.

Hamida was the daughter of the Hindal family’s respected family teacher – a Persian Shia Muslim and a Sufi spiritualist, named Sheikh Ali Akbar Jami. Both of them were invited to the party. Hamida was just 14, but her beauty and demeanour captivated Humayun. Humayun immediately pestered his stepmother Dildar to make a proposal for their marriage. Imagine, Humayun was at his lowest point, having lost his throne recently, and forced to flee from Sher Shah’s forces. How could he even think of adding another wife to his harem? But this was classic Humayun.

Now, Hindal was quite unhappy with the proposal. Some historians speculate that Hindal had a crush on Hamida. But that seems unfounded. Hamida’s and Hindal’s families were so close, that Hindal was concerned for Hamida’s happiness like an elder brother. Would she adjust in an exiled king’s family? On the other hand, he was also worried about the Mughal family pride. In the Islamic tradition, the groom’s family had to offer a bridal dowry befitting their status and honour. How could Humayun, an exiled king, offer a decent dowry? Humayun quickly brushed aside Hindal’s objections, saying they would manage it somehow.

Even Hamida had reservations about the match. Firstly, Humayun was 33, more than twice her age. This objection is documented in Humayun-nama, written by Gulbadan Begum, Humayan’s loving step sister. It’s recorded Hamida saying “I shall marry … a man whose collar my hand can touch, and not one whose skirt it does not reach”. Secondly, he already had a huge harem with many wives. Would he treat her well? When summoned by Humayun’s family, Hamida played hard to get. She said she had already paid respects to the emperor, and it was a sin to appear twice before the king.

But this was a battle Humayun was not willing to concede. He kept pursuing her with a determination that he had not even shown in war! Again, that was typical Humayun. Hamida held out for about 40 days, and in all that time, Humayun remained steadfast. He persuaded Dildar to talk to her. Dildar spoke nicely to Hamida and told her that ultimately she would have to marry someone. Wasn’t it better if that person was a king who was willing and available? Hamida finally agreed. Humayun – an amateur astrologer himself – quickly took out his astrolabe and personally fixed an auspicious time for the wedding. The wedding was joyously celebrated, and they became an inseparable couple. Thereafter, she discarded all her reservations and never left his side, despite extreme hardships.

Humayun was still on the run, and soon they had to leave Thatta for another safe haven. The heavily pregnant Hamida travelled with Humayun across the Thar desert. On the way Hamida’s horse collapsed, and there was no extra horse. Humayun gave his horse to her and travelled on a camel with the others. Finally, they reached Amarkot where the local Rajput lord gave them shelter. Hamida soon delivered a healthy baby boy at the Rajput Lord’s house.

Humayun had great belief in astrology and mysticism. Once when Humayun was despondent, it is said that a spiritual man appeared in his dreams. He predicted that Humayun would get a son who would rule the world and advised to name him Akbar. The healthy baby boy born to Hamida and Humayun was none other than the great Akbar, the heir to the Mughal throne.

But there was no time to waste. Hamida was forced to leave the infant Akbar in Amarkot and flee to Persia. Askari (another step brother of Humayun) and his wife took Akbar to Kandahar to raise him. It must have been particularly heart-wrenching for Hamida to leave behind her new-born son, but her duty was to be with her husband.

The couple reached Persia where they were welcomed by the Shia king Tahmasp-I. Humayun was a Sunni Muslim, but Hamida was a Shia. This perhaps made Tahmasp kinder towards Humayun. He promised to help Humayun in his battles, if Humayun converted to the Shia faith. Humayun reluctantly agreed. Meanwhile, Humayun’s other brothers, Kamran and Askari (Akbar’s guardian) turned hostile in Afghanistan. So with Tahmasp’s support Humayun conquered Afghanistan defeating them, but his loyal brother Hindal was killed in action. After years of separation, Humayun and Hamida were joyfully reunited with Akbar.

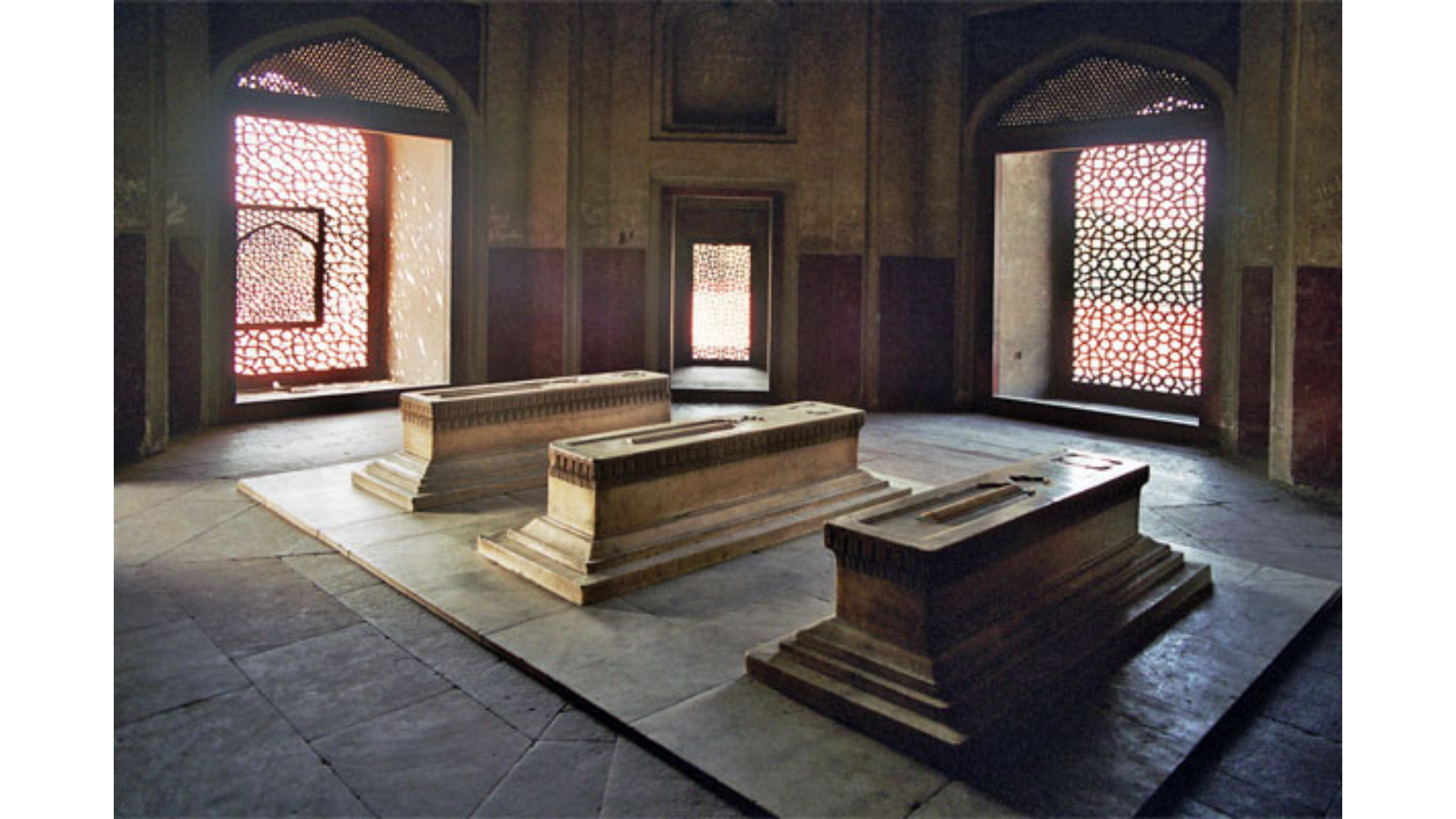

In 1555, Humayun recaptured Delhi and became emperor again. Sadly, Hamida’s joy was short-lived. Humayun died within a year in a freak domestic accident. But Hamida lived on for nearly 50 years more. She and Humayun’s step sister, Gulbadan went on a pilgrimage to Mecca – the sacred duty of all Muslims. As Queen Mother, she made significant interventions in politics, first when Akbar was an infant ruler, then when he ousted his regent Bairam Khan and later on behalf of her grandson Jahangir. Akbar always treated her with great respect and honour. When she died in 1604, she was buried with honours at Humayun’s Tomb.

Humayun became the Mughal emperor under a Mongol system of succession called Coparcenary inheritance. It did not prevent Humayun’s brothers from fighting with him. Watch this short video about the Mughal succession system that led to brutal fratricidal wars in successive generations: The triumphs and tragedies of Shah Jahan

You may also like this story about Humayun’s great-grandson Shah Jahan: How Shah Jahan seized the Mughal throne

Image Attribution

1. Humayun’s Tomb – By Muhammad Mahdi Karim – Own work, GFDL 1.2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20154725

2. Humayun portrayed in a painting circa 1875 – By LACMA – https://collections.lacma.org/node/172754, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7908166

3. Hamida Banu from a 19th century painting – By Unknown artist – http://www.indianminiaturepaintings.co.uk/Lucknow_Hamida-Banu-Begum_000495.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21999450

4. Humayun with Tahmasp at Isfahan (from a painting at Chehel Sotoun Palace) – By Muhammad Mahdi Karim – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22211951

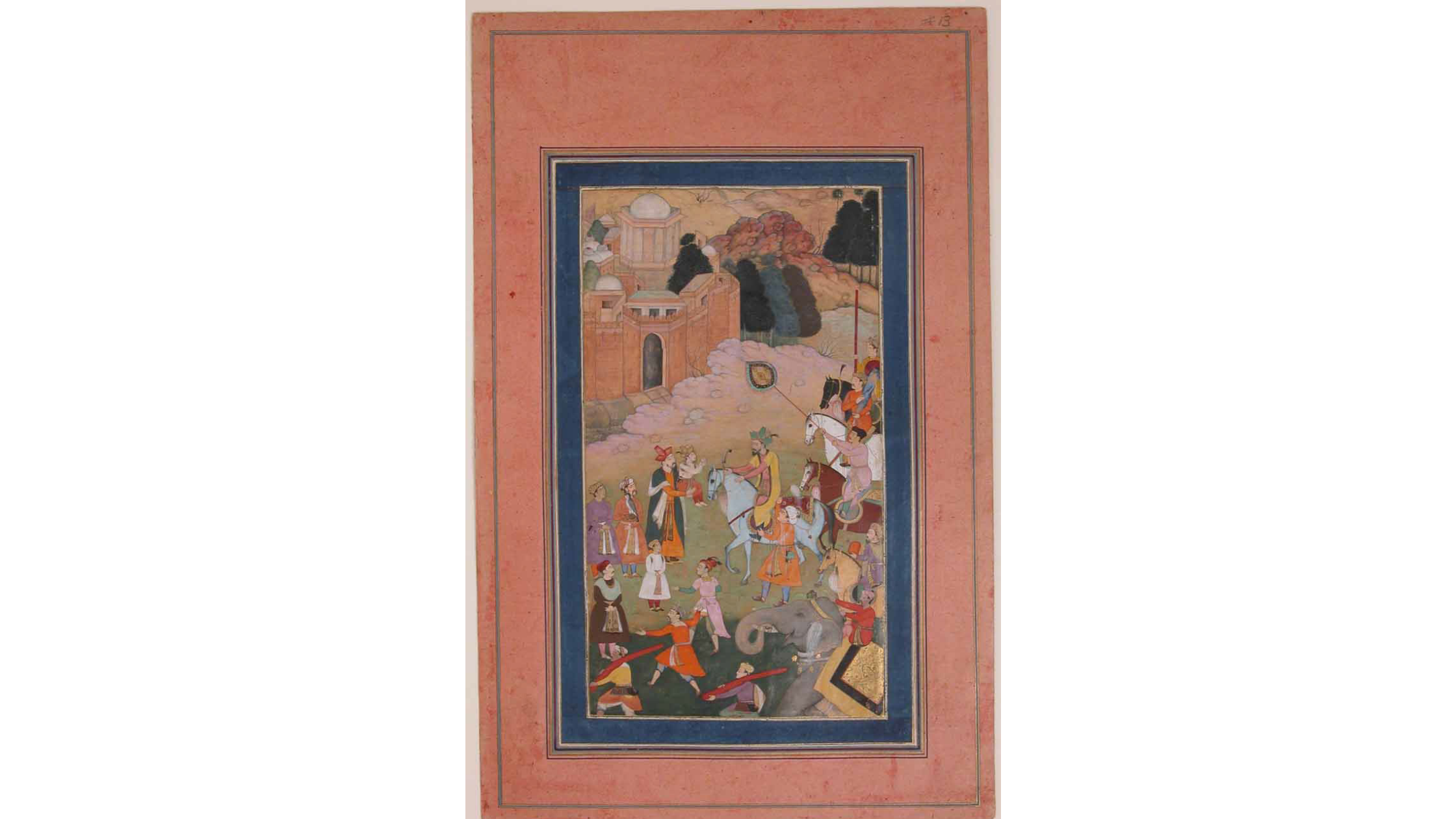

5. Akbar reunited with Humayun, painting from the early 17th cent. – By Reign:Jahangir (1605–27) – https://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/140005731?rpp=20&pg=1&ao=on&ft=humayun&pos=5, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21740261

6. One of these is believed to be Hamida’s cenotaph – By Baldiri – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3381060

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020