Buddhism in India was in its golden age between the 4th century BCE and 6th century CE. Asoka the great, a powerful Indian Emperor had converted to Buddhism after a life changing event and sent missionaries to spread the religion far and wide. Not long after that, Buddhism was patronised even by Hindu dynasties like the Satavahanas and Guptas, and it inspired unique contributions to art and architecture. Indian preachers were spreading Buddhism all over Asia. But strangely, while Buddhism flourished elsewhere, it almost disappeared in India by the 13th century CE. The grand art and architecture it had inspired lay forgotten under layers of earth. Until one man named Colin Mackenzie made a spectacular discovery.

[Detour: Watch the story of how Ashoka used ancient stone caskets containing Buddha’s cremated remains to spread Buddhism across the sub continent]

[Detour: You can read more about the Satavahana art here

What made the Satavahana dynasty so powerful? Read that story here ]

Born in an obscure Scottish town, Mackenzie discovered that mathematics fascinated him. Chewing his way through mathematical tomes he discovered the mathematics of the ancient Hindus and was spellbound. Only a trip to its roots in India would satisfy him.

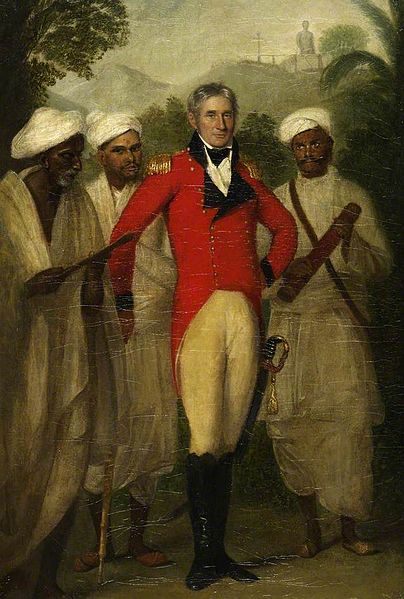

He joined the army of the British East India Company and because of his flair for numbers was appointed to the Engineering Corps. He arrived in India at Madras (Chennai) in 1783. India fascinated him even beyond mathematics, and he became hooked to Indian art, culture and history. He was neither a historian nor an archaeologist but in India, he became the best of those. He travelled throughout the Indian subcontinent documenting its history, literature and architecture. He recorded everything he saw through sketches. He also managed to collect and store important artefacts. In 1797, he travelled to Amarāvatī and discovered a Stupa. By now Buddhism had practically disappeared from India and Mackenzie at first thought the ruins belonged to the Jain faith. But he was still on military duty, he found no time to explore the amazing ruin. He notified his superiors about the find and moved on to other things.

In 1815, Mackenzie was appointed the very first Surveyor General of India. Amarāvatī called to him again. He spent four years between 1816 and 1820 studying the ruins and deploring the neglect that had befallen them after his discovery. Bricks from the precious ruins had been carried away for building work and irresponsible excavations had ruined the structure. Painstakingly Mackenzie further excavated the site and drew sketches and plans of what the original structure must have been like.

But he didn’t manage all this on his own. A key factor in Mackenzie’s success was that he involved bright Indian assistants and directed them well. Early in his career, he recruited Cavelly Venkata Boraiah, an Indian scholar who spoke impeccable English, and later his brother, Cavelly Lakshmaiah. They were fine researchers with a knack for getting inside information from the locals. Mackenzie’s team had at least 17 Indian scholars like the Cavelly brothers.

Mackenzie spent nearly 40 years in India, and never returned home. He was busy here, passionately assembling the largest collection of Indian artefacts by any European: more than 1568 literary manuscripts, 8076 inscriptions, 79 plans, 2630 drawings, 6218 coins and many other antiquities. He probably dreamt of returning home and enjoying his collection quietly. That never happened. He died suddenly in his adopted country in 1821. He left 5% of his estate to his dear colleague Lakshmiah and the rest to his wife. Mrs Mackenzie discovered, to her horror, that all his savings had been spent on the collection. Desperate, she offered to sell the collection to the East India Company for Rs.20,000. When the company assessed the collection, they were astounded by its value. They paid a generous Rs100,000 for it, and Mrs. Mackenzie retired comfortably!

Today most of Mackenzie’s collection is in the British Museum or owned by the British Library. His discoveries from Amaravati however, were moved some years after his death to Madras (Chennai). Today, you can see some of these beautiful treasures in the form of limestone carvings at the Amaravati Gallery of the Government Museum in Chennai.

Wondering what these carvings were all about? Download the Storytrails App and listen to the Stone Sculpture Galleries Audio Tour.

{You can also learn about the story of the Madras Museum here}.

Amaravati artefacts are also displayed in the British Museum and a few other museums in India and the world. The World Corpus of Amaravati Sculpture is an international project that allows scholars of all nationalities to access information from museums and perform interdisciplinary research collaboratively. Thanks to one man, Colin Mackenzie, India and the whole world now share the joy of Buddhist art.

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020