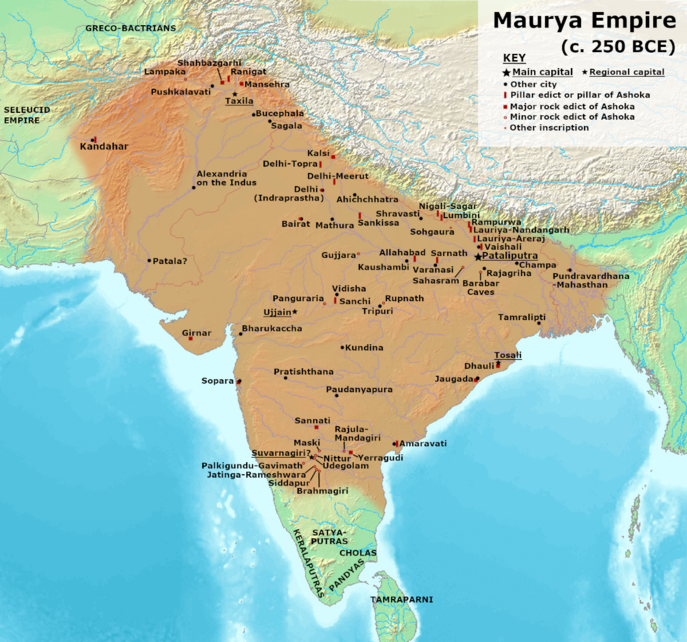

The year was 261 BCE, and in India the Mauryan Emperor, Ashoka the Great was planning to go to war with the neighbouring state of Kalinga. By this point Ashoka had been king for 8 years and was known for his ruthless efficiency. He had killed his brothers to secure his throne, crushed rebellions and imprisoned and tortured his enemies. Once certain of his power, he had decided to expand his kingdom through conquests. In the first seven years of Ashoka’s rule, the Mauryan empire grew enormous: stretching all the way from modern-day Afghanistan in the north west to Bangladesh in the east.

Kalinga was the next natural choice for an ambitious emperor. It was a large, independent, wealthy kingdom that sat right between Ashoka’s empire and the rival kingdoms of the southern peninsula. Mauryan emperors before Ashoka had tried to capture Kalinga and failed. To a king set on making a name for himself, Kalinga was irresistible. But it was a much harder conquest than Ashoka expected. The first armies he sent out were soundly defeated. Kalinga had a formidable military force of their own. Ashoka realised that nothing short of his full army would be enough, so he scaled up and attacked again. Still, the people of Kalinga fought back fiercely. The war raged on for one whole year as battle after bloody battle was fought. Eventually though, Kalinga could not match the sheer size of the Mauryan army, with its seemingly endless supply of soldiers.

Kalinga fell. At the end of it all 10,000 Mauryan soldiers were dead. In Kalinga, the numbers were far greater: 100,000 by one account. When Kalinga was finally annexed, the war had touched the lives of every single person in the kingdom. It also had a profound impact on Ashoka. Up until that point, Ashoka, was considered a rather callous king. Kalinga changed everything.

Here’s one account of what happened next:

“…On conquering Kalinga, the Beloved of the Gods (Ashoka) felt remorse, for, when an independent country is conquered the slaughter, death, and deportation of the people is extremely grievous to the Beloved of the Gods, and weighs heavily on his mind…” (Ashokan Edict XIII)

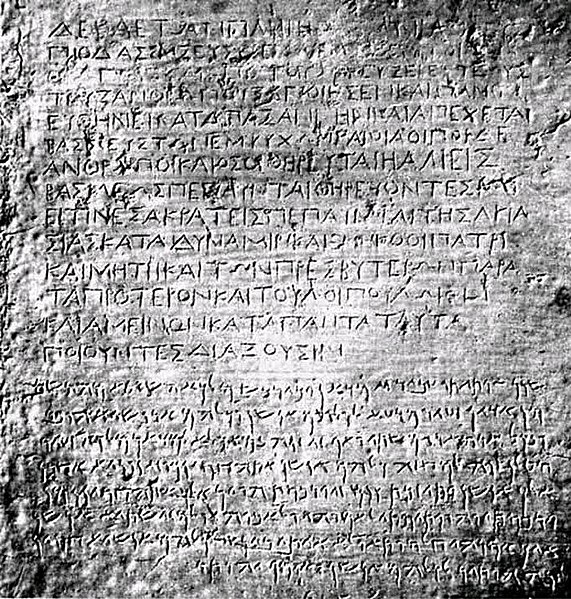

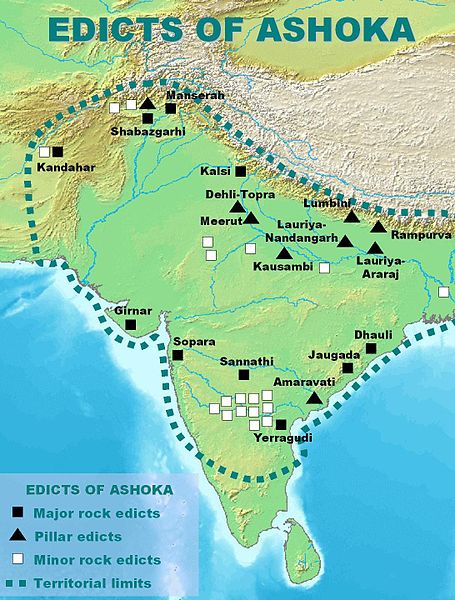

This account is Ashoka’s own and shows his deep remorse at the destruction he had caused. Such inscriptions in the form of stone edicts were placed in different parts of his kingdom. 33 of these famous edicts carved into rock boulders, cave walls and pillars in different parts of his empire have survived till today. You can find these carvings all over India, and in parts of Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan. They were written in several languages including Prakrit, Aramaic and Greek.

Want to know more about the origins of Buddhism, and its influence in India? Download the Storytrails App and take the Audio Tour around the Stone Sculptures Gallery of the Government Museum in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Discover stories from some of the oldest Buddhist monuments built in Ashoka’s time.

The edicts tell us a lot about the kind of king Ashoka became after Kalinga and his relationship to Buddhism. Some historians suggest that it was after the war in Kalinga that Ashoka converted to Buddhism. Others say, that he was always a Buddhist, but it was only after the war that he paid any real attention to what being a Buddhist meant. The carvings, interestingly enough, concentrate not so much on Buddhism as a religion, but more on the philosophical implications of trying to live a righteous life. Ashoka wanted his people to live their lives bound by the Buddhist idea of Dhamma or duty and righteousness. The edicts were meant to give his people directions to lead such a life.

Here’s an excerpt from the English translation of the Kandahar Edict above:

“Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King

Piodasses (Ashoka) made known (the doctrine of)

Piety … to men; and from this moment he has made

men more pious, and everything thrives throughout

the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing)

living beings, and other men and those who (are)

huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted

from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they

have ceased from their intemperance as was in their

power;” (Trans. by G.P. Carratelli)

Ashoka appears to have believed in leading by example. He also donated generously to Buddhist monasteries and, by one account, built 84,000 stupas in different parts of the country. He is also credited with the spread of Buddhism beyond India by sending Buddhist missions as far as the Mediterranean. Today Buddhism has around 488 million followers around the world and it all started with Ashoka.

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020