The main base of the Western Naval Command in Mumbai is, like all naval bases, named as a ship would be. It’s called the INS Angre. If you ever have the pleasure of visiting the naval base, you can spot an imposing statue taking pride of place. It is the statue of a fierce warrior of the Maratha Empire, sporting an even fiercer moustache. This is the base’s namesake, Admiral Kanhoji Angre, one of the Indian Navy’s historical heroes.

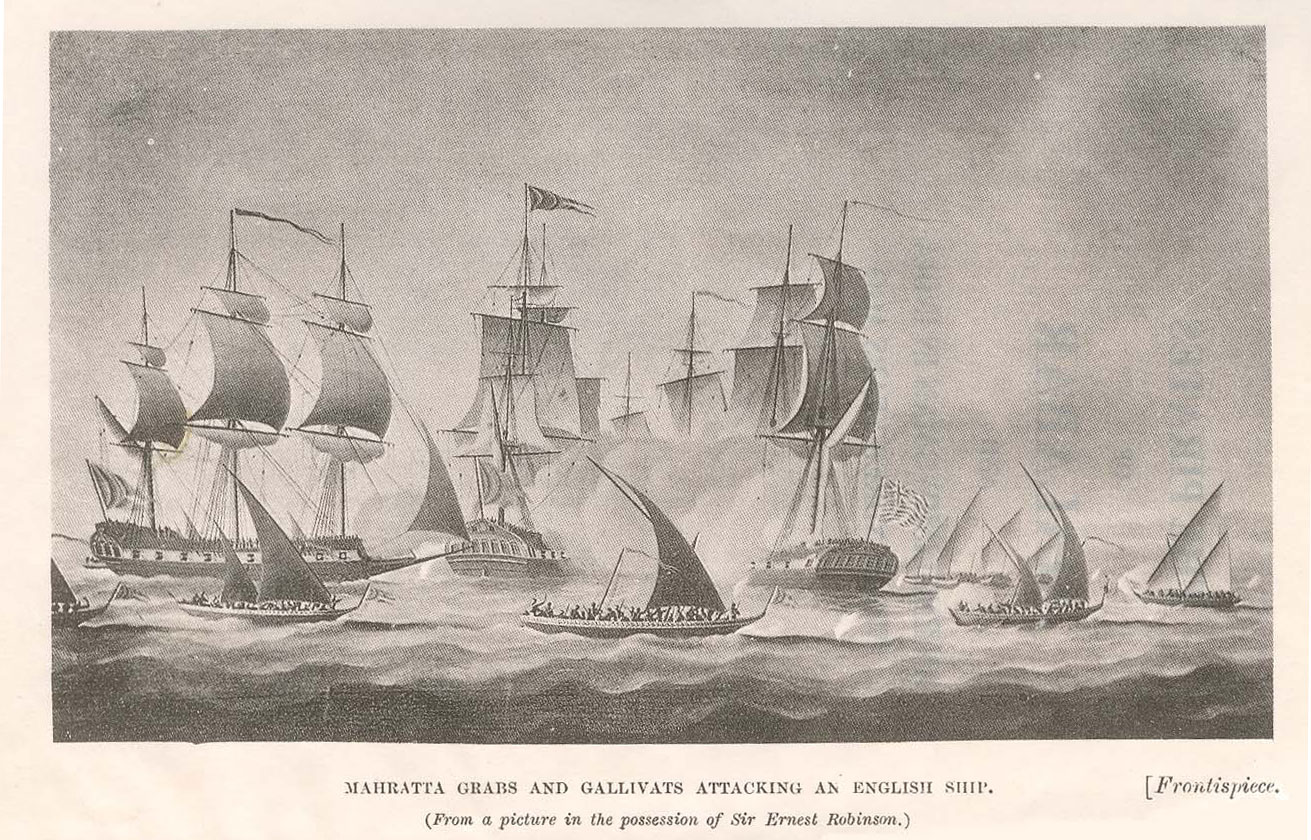

Angre’s rise to power came just as the 17th century was ending and the 18th was beginning. This was after the fall of Shivaji and his sons when the Maratha Empire was in the middle of a battle for succession between Tarabai, Shivaji’s daughter-in-law, and Shahu Bonsle I, Shivaji’s grandson. Both sides wanted Angre, and he played this to his advantage. He was able to wrangle concessions that essentially made him an independent ruler with multiple coastal forts. According to Clement Downing, an employee of the English East India Company (EIC) who was a witness to Angre’s many naval campaigns, the legendary figure started with just a few men and some fishing boats. Then, he captured trading ships and kidnapped a few soldiers from the Maratha armies to sail them. It seemed he had a talent for naval strategy and, soon enough, in 1699, at the young age of 30, Angre was appointed sarkhel or admiral in the Maratha fleet.

The ethnicity of Kanhoji Angre (or Angria) is bitterly contested among historians. Some claim that he was of Rajput descent. Others point to sources that claim he had Ethiopian (or Siddi) blood. Yet others say he was a Koli, belonging to the fishing community indigenous to the land around Bombay. Some also claim he was a Maratha. But regardless of what’s true, Angre’s origins didn’t hold him back from becoming one of the most powerful men on the Western coast of the Indian subcontinent during the early 18th century.

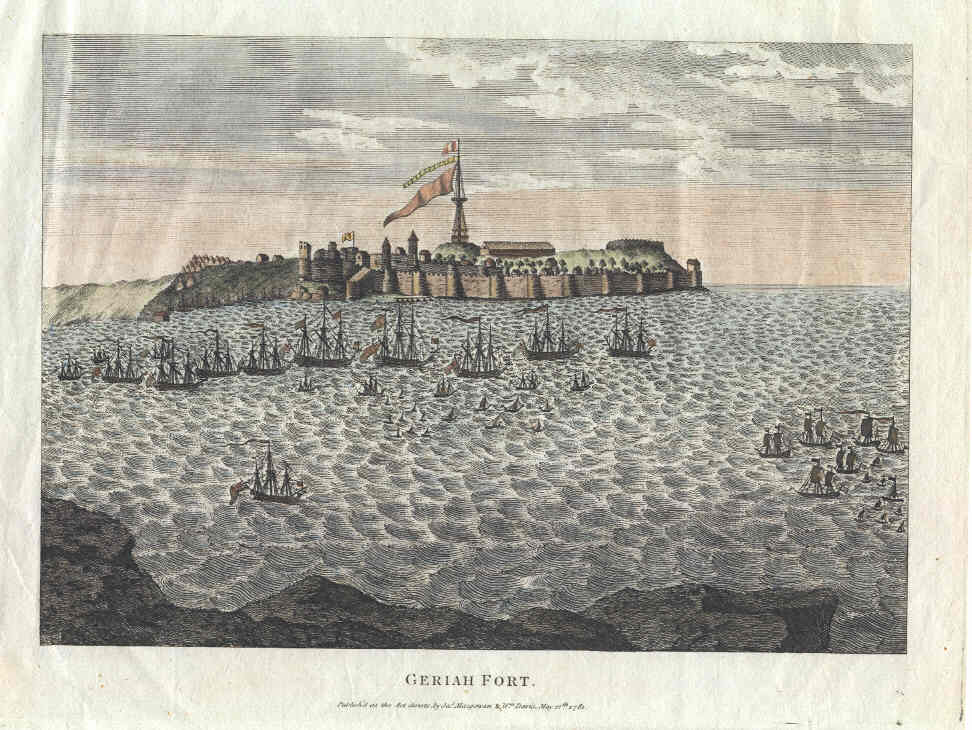

The capital of Angre’s new kingdom was the fort of Vijaydurg (also known as Gheria), on the southern edge of Maharashtra’s coastline. But the land around his coastal forts was mostly barren and so the admiral had to sustain his little kingdom through trade, selling protection passes to commercial ships, and indulging in what the colonial powers termed “piracy”. According to one historian, the EIC spent more than £50,000 annually to protect their goods and ships from Angre and his “pirates”.

Unlike many of the other Maratha rulers who saw the Mughals as their main enemy, Angre was very aware of the looming threat of the EIC. He was a perennial thorn in their side. Despite the Company launching multiple full-scale assaults against him, Angre never lost a single fortress as long as he lived.

In 1718, the Company got hold of a Portuguese defector who had escaped from Angre’s clutches. With his information, they deployed a force with around 50 ships and 2000 sailors but even then, they failed to defeat Angre. Three years later, an Anglo-Portuguese alliance with an even larger army tried again to take Vijaydurg. This time, they had more than 6000 soldiers attack over land during low-tide and had 300 big guns attacking from ships at sea. It was a huge army for such a small fort, and yet, they lost out to Angre’s tactics and Vijaydurg’s natural defences.

Kanhoji Angre died in 1729, leaving behind five sons who ended up squabbling over property and succession. The Company took advantage of this infighting and played sons off against each other. Only one son, Tulaji Angre, held out. But even he was defeated in 1754 when Peshwa Balaji Rao, the Maratha ruler, began to suspect his loyalty and allied with the Company against him.

Angre is mostly forgotten today. Outside of naval bases like the INS Angre, there’s little testimony to the most feared admiral of India’s Western coast. But travellers can still see a beautiful statue of Kanhoji Angre if they visit Alibaug, a popular weekend getaway near Mumbai where Angre was buried.

Want to hear more about Mumbai’s history? Join Storytrails on ‘The Bombay Story’ walking tour and learn all about the interesting people who helped build Mumbai.

Archives

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013

Featured Posts

- Tales that pots tell: Keeladi excavations AUGUST 18, 2021

- The Last Grand Nawab: Wallajah FEBRUARY 10, 2021

- How Tej Singh became Raja Desingu of Gingee FEBRUARY 5, 2021

- How Shahjahan seized the Mughal throne JANUARY 28, 2021

- Alai Darwaza – Qutub Minar Complex, Delhi NOVEMBER 21, 2020

- Marking History through British buildings NOVEMBER 17, 2020

- The last great queen of Travancore NOVEMBER 7, 2020

- Brahmi and the evolution of scripts OCTOBER 15, 2020

- The Cambodian King of Kanchipuram OCTOBER 14, 2020

- James Prinsep – the man who read the writing on the wall OCTOBER 10, 2020

- Mariamman – the Village Goddess who travelled SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

- Misnamed Monuments of Mamallapuram SEPTEMBER 28, 2020